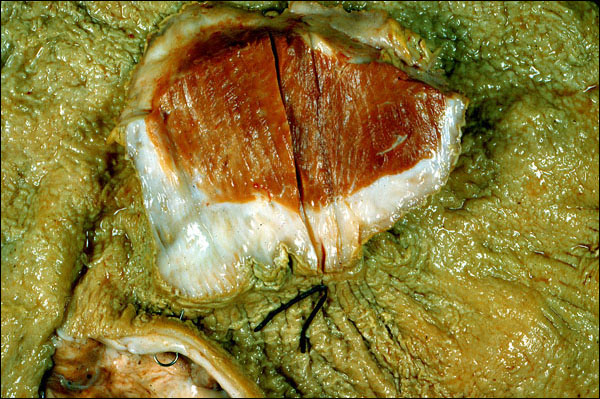

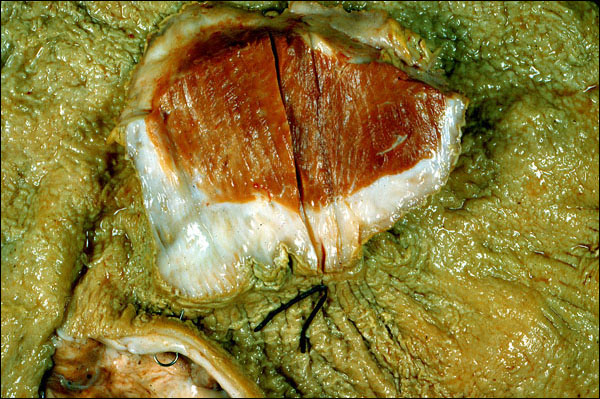

Fibrinous pericarditis, chronic-active

Click picture to enlarge. Close window to return

The inflammatory process described, and its outcome, would be the same in a human being, although the circumstances causing the infection would, hopefully, be different. Cattle are not the most intelligent animals in the world. They often will swallow a nail if it is contained in their feed. Their anatomy is such that ingested nails gravitate to a compartment at the front of their stomach, which is just on the other side of the diaphragm from the heart. Often, a nail will puncture the wall of the stomach and the adjacent diaphragm, penetrating the pericardium. This creates a channel for stomach contents to enter the pericardium and pleural space, which invariably causes inflammation that is severe enough to result in the deposition of fibrin. Thus, the exudate is a fibrinous or, more usually, fibrinopurulent one. This particular case is of interest, because the nail (at six o'clock) had been there a long time. As a consequence, chronic-active fibrinous pericarditis developed. The yellow, shaggy material on the outer surface of the pericardium is the most recently deposited fibrinopurulent exudate. The cow also had chronic-active fibrinous pleuritis. But those conditions didn't directly kill the cow. The brown heart muscle can be seen at the upper center of the photograph, where a tangential cut has been made through the pericardium, which was adherent to the external surface of the heart. There is a white band that separates the muscle from the fibrinopurulent exudate. That band is scar tissue, which formed as the exudate organized in this chronic-active process. (The process must be categorized as chronic, because of the scar tissue, and active, because it is still forming fibrinopurulent exudate.) A characteristic of scar tissue is that it contracts as it matures. This scar tissue had contracted to the extent that it caused loss of cardiac functin, it consricted the heart, causing animal to die of congestive heart failure.